Landscape Ecology - Lecture

Notes

Landscape Pattern and

Ecosystem Processes

[From Bailey 1996]

I. Mechanisms for

movement of energy, materials and species in landscape mosaics

A. Major vectors

(1) Wind

- Carries heat energy, water, dust, pollutants, nutrients,

propagules, organisms, etc.

(2) Water

- Carries mineral nutrients, seeds, insects, sewage,

fertilizers, pollutants, etc.

(3) Flying animals (e.g., birds, bats, bees)

- Carry fruits, seeds, spores and insects in feathers, feet,

and the gut

(4) Ground animals (e.g., mammals, reptiles)

- Carry seeds, fruits, spores, insects, etc.

(5) People (use of vehicles)

- Carry organisms, seeds, fruits, spores, insects, nutrients,

etc.

B.

Main forms (or forces) of movement

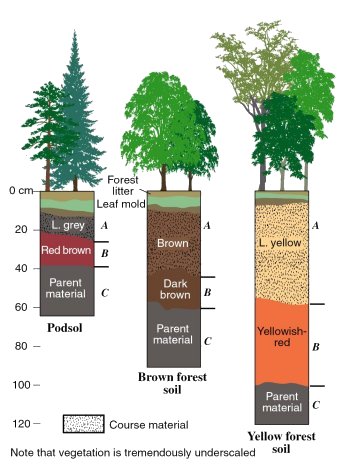

II. Landscape

pattern and spatial distribution of energy and materials

- The spatial distribution of biomass, ecosystem productivity,

and biogeochemical processes are closely related to the spatial

pattern of the landscape (e.g., vegetation types, hydrological

regime, topographic variation, disturbance regime, climatic

variation, etc.)

- Main causes:

- Climatic factors (temperature, precipitation)

- Soil heterogeneity

- Topographic variations

- Animal activities (e.g., selective foraging)

[From Bailey 1996]

- Example: Ecosystem properties and processes vary

spatially across the landscape.

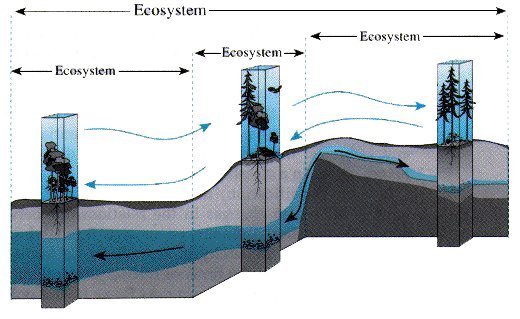

III. Movement of

nutrients and energy among ecosystems is affected by landscape

pattern

- Both the composition and configuration of landscapes (e.g.,

land cover types, diversity, connectivity, and boundary

characteristics) affect flows of materials, energy, and

organisms in landscape mosaics.

- Flows of different types affected by and affect landscape

pattern

- Ecosystem processes: primary productivity,

biogeochemical cycling, decomposition

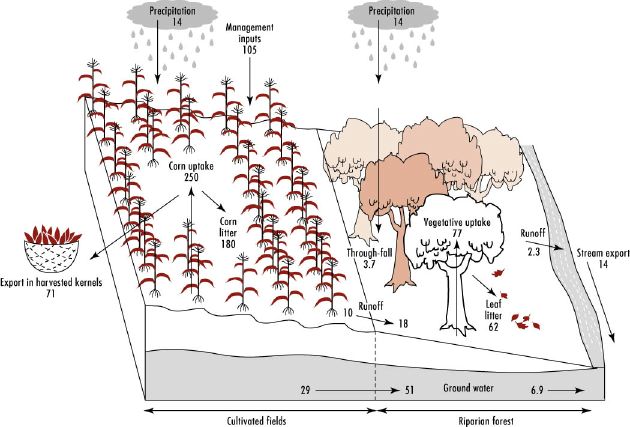

Figure caption: Movement of nutrients and major

pathways between ecosystems on the Rhode River watershed,

Maryland (Drawn based on data from Peterjohn and Correll

1984; cf. Turner et al. 2001)

- Margalef's (1963) hypothesis: In considering flows

between adjacent ecosystems or elements, the younger may

operate as a source of energy or material, and the more mature

as a sink or recipient (also see Risser 1990).

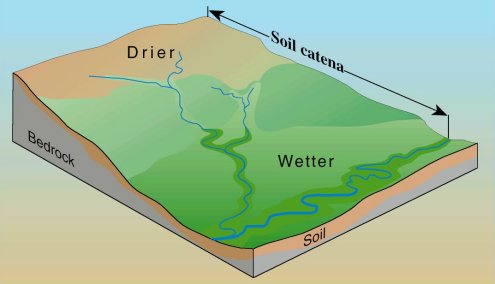

- Example: Lateral flows in landscapes and effects on

ecosystem processes

- Stury area and field sampling

- The

universal soil loss equation (USLE):

A = f(R, K, L, S. C) or:

A = f(R, K, L, S. C, P)

A - amount of soil eroded

R - rainfall intensity

K - soil erodability factor

L - length of the slope

S - angle of the slope

C - vegetation cover

P - supporting practices factor

The Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) does not account for

landscape heterogeneity, a measure of spatial configuration or

juxtaposition of landscape units needs to be incorporated

(Risser 1990). Efforts have been made to incorporate

landscape heterogeneity into the universal soil loss equation,

resulting in revised universal soil loss equations (RUSLE).

- Example:

Land use and land cover change alters the spatiotemporal

pattern of ecosystems (e.g., urbanization)

IV. Effects of landscape

fragmentation on ecosystem dynamics

[Excerpt from J. Wu (2009). Ecological dynamics in fragmented

landscapes. In: Simon A. Levin (ed). Princeton Guide to

Ecology. Princeton University Press, Princeton.]

Ecosystem

ecology, the study of energy flow and material cycling

within an ecosystem composed of the biotic community and its

physical environment, traditionally has adopted a systems

perspective, which emphasizes stocks, fluxes, and interactions

among components without explicit consideration of spatial

heterogeneity within the system and effects of the landscape

context. With the rapid development of landscape ecology

since the 1980s, more and more ecosystem studies have adopted a

landscape approach that explicitly deals with within-system

spatial heterogeneity and between-system exchanges of energy and

matter.

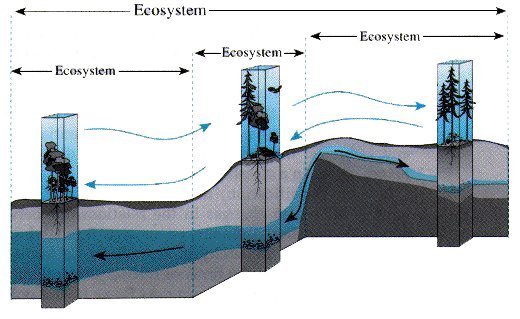

An increasing

number of recent studies have shown that landscape fragmentation

can influence ecosystem dynamics in several ways. First, the loss and creation

of patches directly change the spatial distribution of pools and

fluxes of energy and materials in the landscape (e.g., biomass,

ecosystem productivity, nutrient cycling, decomposition,

evapotranspiration). Second,

the altered configuration of landscape elements, particularly

introduced edges and boundaries, may not only affect the flows

of organisms but also the patterns of lateral movements of

materials and energy within and among ecosystems (e.g.,

hydrological pathways and erosion-deposition patterns). Third, landscape

fragmentation can affect ecosystem processes through

microclimatic modifications due to altered surface energy

balance (e.g., changes in albedo, radiation fluxes, soil

temperature, soil moisture, wind profile and pattern) especially

near the boundaries of remnant patches (edge effects). Fourth, all the effects of

landscape fragmentation on population dynamics and species

persistence have bearings on ecosystem processes because both

plants and animals play an important role in ecosystem

processes.

Landscape approach to ecosystem dynamics

A landscape

approach to ecosystem dynamics is characterized by the explicit

consideration of the effects of spatial heterogeneity, lateral

flows, and scale on the pools and fluxes of energy and matter

within an ecosystem and across a fragmented landscape (Turner

and Cardille 2007). This new approach to ecosystem studies

highlights the fact that ecosystems are neither homogeneous

internally nor closed externally. Such a perspective seems

in sharp contrast with the traditional equilibrium view that

ecosystems are self-regulatory, self-repairing, and homeostatic,

and is particularly appropriate when fragmented landscapes are

considered. Guided by this spatial approach, several key research questions have

emerged: How do the pools of energy and matter and the rates of

biogeochemical processes vary in space? What factors

control the spatial variability of these pools and

processes? How do land use change and its legacy affect

ecosystem processes? How do patch edges, boundary

characteristics, within-system spatial heterogeneity, and the

landscape matrix influence ecosystem dynamics and

stability? How do ecosystem processes change with scale

and how can they be related across scales (i.e., scaling)?

How do the responses of populations and ecosystem processes to

landscape fragmentation interact? How do the composition

and configuration of fragmented landscapes affect the

sustainability of landscapes in terms of their capacity to

provide long-term ecosystem services?

A landscape

approach to ecosystem dynamics promotes the use of remote

sensing and GIS in dealing with spatial heterogeneity and

scaling in addition to more traditional methods of measuring

pools and fluxes commonly used in ecosystem ecology. It

also integrates the pattern-based horizontal methods of

landscape ecology with the process-based vertical methods of

ecosystem ecology, and promotes the coupling between the

organism-centered population perspective and the flux-centered

ecosystem perspective.

V. Future directions

Back to Dr. J. Wu's Landscape Ecology

Homepage